Emma's SURE Experience in the Smyth Lab

This summer I was excited to be added as an undergraduate researcher to Smyth Labs. I have always been interested in bringing aspects of social and natural sciences together, and this project was no different. The project was composed of two parts: a series of experiments to analyze the antimicrobial activity of honey, and a series of meetings with urban beekeepers and parks that promote pollination in New York City.

Part 1: Hitchhikers in Honey

Our primary goal was to assess the antimicrobial activity of various honeys collected in the US. A decent amount of research has been done on honey and its topical application to wounds as well as the enzymatic activity that could make honey an ideal source of antimicrobial activity. The honey samples were diluted in water and incubated to see what microorganisms called the sticky substance home.

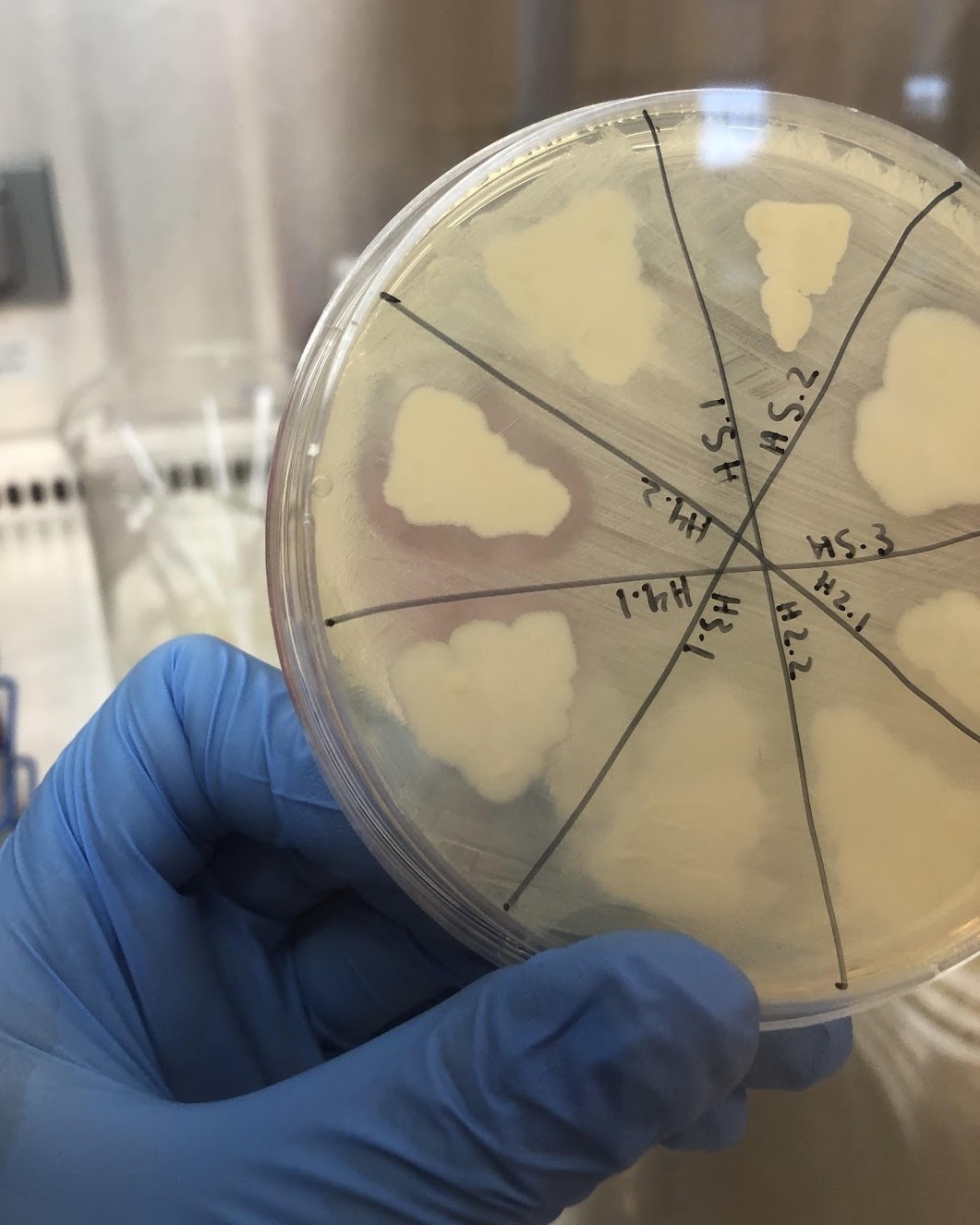

Image 1 - Plate with bacterial colonies

The microorganisms that developed were identified as bacteria through a 16S PCR, and some of them had incredible antimicrobial effects against Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis. The honeys that had the most inhibitory impacts against these gram positive bacteria were the Manuka honey from New Zealand, and a honey sample from Tennessee (Image 3).

Image 2 - Zones around bacteria isolated from honey samples, on a plate with Staphylococcus aureus

Manuka honey is well known as an antimicrobial substance which is believed to originate from the nectar of a specific plant, Leptospermum scoparium, or simply, the Manuka Plant (Image 4).

The infamous Manuka plant, the nectra allows for the creation of the powerful Manuka Honey.

What exactly makes this kind of honey such a good antimicrobial resource? Based on our research the bacteria that grew from the honey may provide insights into this. And this finding may even indicate a link between honey samples from across the globe. Of course that is simply a hypothesis of what could emerge from the sequencing that will be conducted on the honey samples of interest. Based on the literature on this subject, I am still expecting that the antimicrobial impacts of bacteria grown from honey is still just one piece to an incredibly complex ecological puzzle.

This project was important to me for a few reasons. The most obvious was my own discomfort in the lab environment. Although I had taken a class that focused on a lot of the same skills I employed in this project, the lab still felt like a foreign place. It didn’t take long to figure out where things were and the general way things happen in the lab. Although I still feel like a trainee, so to speak, I feel far more equipped with microbiology lab skills than I did two months ago. The second reason is because I love bees. I keep up with the latest news on colony collapse disorder and am very fearful that one day there will be a world without bees, leaving plants and crops vulnerable. Not only do I also love honey in my tea or on my toast, I believe that conducting research about the importance of bees and honey is essential to bringing attention to the problem and making a change.

Part 2: Driving Pollination

The second part of this project was something that I felt much more comfortable with, even though I am just beginning. I planned on conducting research with urban beekeepers and nonprofits in New York City to see how communities engage with beekeeping. I was also interested in asking beekeepers about the benefits of raw, unprocessed honey. Unfortunately, this portion of the project was postponed because of a delayed IRB review. As an anthropology major I am very aware and careful of the ethical concerns when talking to humans. I always want human subjects to be protected whether I am asking them one question, or talking to them for 2 hours. Once the approval came in I began reaching out to various independent hives, non profits, and community gardens in New York City to begin this portion of the research.

So far I have only been able to speak with a few people at the Washington Square Park Conservancy about the work they are doing to attract pollinators. They believe in the importance of attracting insects to the park and educating kids and adults alike about the essential work these insects do. I spoke with the youth coordinator about the class she teaches the first Wednesday of every month. I also spoke extensively with the gardener who told us about the plant overhaul they did this season to bring in more pollinating insects.

– Emma Letcher

A specific part of Washington Square Park designed to attract pollinating insects.